Choosing the Right Breed for Your Backyard Flock

After careful thought, you have decided you are ready to acquire a small flock of backyard chickens. So, now what? If you live inside city limits, first check with your municipality to make sure poultry are allowed where you live. Some locations have “no livestock” clauses that will ban you from keeping poultry. Even if the city allows chickens, make sure that your subdivision or homeowners’ association does not impose a ban on keeping chickens.

You do not want to spend a lot of money on coops, pens, and chickens only to find out later that you can’t have chickens. Do your homework before becoming too heavily invested monetarily and timewise in your chicken project. Once you have the go-ahead to keep chickens, the fun begins. Let’s take a look at what you need to know when choosing to keep backyard chickens.

Have a Goal in Mind

Know where you want to finish before you even start. Think things through and have a goal in mind as you begin planning your project. Determine where you want to focus your efforts. You must decide if you are interested in:

- egg production

- meat production

- dual-purpose production (both meat and eggs)

- fun with genetic diversity—crossing current genetic stock to develop your own unique chickens

- breed preservation—maintaining heritage or rare breeds that are threatened or in danger of becoming extinct

These are decisions you need to make before you start because they will help guide you toward your goal. For example, if you are looking at egg production, how critical is egg fertility? Hens will lay eggs without a rooster once they reach sexual maturity. However, those eggs will not be fertile and will not hatch. If you are selling table eggs, you won’t need a rooster. If you want to hatch your own chicks or provide fertile hatching eggs to others, you will need a rooster (generally, one rooster for every 10–12 hens).

How critical is the shell color? Remember, you can choose from white, various shades of brown, green, and blue. If you are interested in meat birds, do you want yellow or white skin? Do you want your birds to have a large amount of breast meat or produce lots of dark meat? How many birds will you have initially? Will you increase numbers at a later date? If so, you should plan your coop size and pen space accordingly. Will you have standard-size chickens or bantams? Keep in mind that bantams are smaller and will eat less feed. These are all questions you should answer long before your first chicken ever arrives.

| Good-natured |

Oprington Rhode Island Red Naked necks |

|---|---|

| Friendly |

Dominique Araucana Australorp Jersey Giant Delaware Cornish Java |

| Nervous (flighty) |

Leghorn Ameraucana Polish |

| Aggressive |

Ameraucana Modern game |

As mentioned above, chickens come in two sizes: normal-size chickens and bantams. Bantams are, for the most part, miniature copies (about one-fourth the size) of larger breeds. They are often used as ornamental birds, although some are good egg-layers, even though the eggs are much smaller. Chickens are typically classified into various groups based on:

- color

- size

- shape

- location of origin

Some birds are better foragers than others and are better able to find their own food. Active breeds will readily forage in the grass for bugs, tender leaves, and shoots, while the less-active breeds will wait for you to feed them every day. Active breeds work better if you are considering a pasture or free-range production operation. Climate is important where chickens are concerned. Some chickens do better in cold areas, while others do better in hot regions. In most cases, birds with large combs do better in hotter regions, and birds with smaller combs perform better in colder areas. In general, most American breeds do better in colder climates, while Mediterranean breeds do better in hot climates.

There are a few terms that will help you have a better understanding of the chicken business. Class generally refers to a group of birds that come from a common geographical region. Breed refers to differences within a class, such as body shape or size, skin color, number of toes, or feathering on the shanks and toes. Variety refers to birds within a breed that differ in feather color or pattern, or type of comb. For example, there are brown and white Leghorn varieties, based on feather color. All chickens worldwide originated from the Red and Green Jungle Fowl breeds of Southeast Asia.

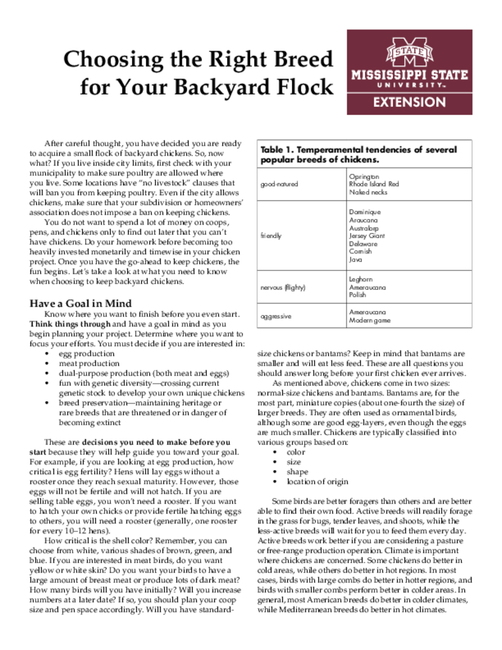

Temperament can be important when selecting chickens. Temperament is a bird’s behavior pattern or “how it acts.” Some breeds are much more nervous, aggressive, docile, or friendly than other breeds. This can impact your selection decisions, especially if you have children who will be helping with the chickens. Table 1 lists the temperamental tendencies of several popular breeds of chickens.

Egg-Laying Birds

Some breeds of chickens have been selected specifically to be good egg layers. These birds may lay 250–300 eggs per year or more. However, these are not good meat-type birds. They tend to be smaller, grow slowly, consume less feed than meat-type chickens, and produce a carcass that has little meat on it. Leghorns are usually the best overall egg layers, although several other breeds produce large numbers of eggs, as well. However, Leghorns will never become meaty. They put all of their effort into laying eggs, not gaining weight.

Eggs can come in several colors including white, various shades of brown, blue, and green. However, the shell color has absolutely nothing to do with the nutritional content or taste of the egg. Brown eggs are no more natural or healthier than white eggs. Brown eggs cost more in the store because hens that lay brown eggs are usually larger and consume more feed than hens that lay white eggs. This additional feed cost is passed on to the consumer, making brown eggs more expensive to purchase. Hens that lay white eggs are usually smaller and consume less feed and are generally preferred by the commercial industry because they cost less to maintain. The diet that the hen receives, not the color of the shell, determines the nutritional content of the egg. Several breeds that are considered good egg-laying birds include:

- Leghorn

- Australorp

- Ameraucana

- Araucana

- Polish

- Sex-links

The Leghorn breed originated in Tuscany, in central Italy. They were first exported to North America in the mid-1800s. They are well known for their egg-laying capabilities. White Leghorns are commonly used as layer chickens in many countries around the world. Adults weigh 4.5–5.5 pounds. There are numerous varieties, although white and brown appear to be the most popular. Leghorns lay eggs with white shells.

Australorps are native to Australia and were developed as a dual-purpose breed with an emphasis on egg laying. Adults weigh 4.5–8.5 pounds. In the 1920s, the breed became popular for breaking numerous world records for number of eggs laid. The most popular color in the U.S. is black, although other varieties do exist around the world. Australorps have good mothering instincts and lay brown eggs.

The Ameraucana breed was developed in the United States in the 1970s. It derives from the Araucana breed brought from Chile and was bred to retain the blue egg gene. Adults weigh 4.5–6.5 pounds. There are eight color varieties recognized in the American Standard of Perfection. The breed’s outstanding highlight is the eggshell color that comes in various shades of blue.

The Araucana breed is believed to have originated in the Araucania region of Chile. Araucanas may have tufts of feathers on the ears. They may also be rumpless, without a tail or tailbone. Lethal genes cause the missing tail and feather tufts on the ears. Therefore, not all birds will display these traits. Adults weigh 4.5–7 pounds. They are good egg layers and will lay approximately 250 blue or green eggs per year.

The exact origins of the Polish breed of chicken are unknown. Polish chickens are known for the crest of feathers on their heads. They are excellent egg layers, although they have poor mothering instincts and rarely go broody (stop laying and begin incubating eggs). Adults weigh 4.5–6 pounds. The crest of feathers on their heads obscures their vision, so they are at greater risk of predation (especially from aerial predators) if allowed to free range. They have a temperament that is somewhat nervous and flighty, and they are easily surprised. They are similar to Leghorns in both size and shape. Polish chickens lay white eggs.

Sex-links are crossbred chickens whose color at hatching is differentiated by sex, making chick sexing a much easier process. Sex-links are extremely good egg layers and can often produce 300 eggs per year or more. The color of egg varies depending on the mix of breeds involved. Many common varieties are known as black sex-links (Black Stars) and red sex-links (Red Stars). Black Stars are a cross between a Rhode Island Red or New Hampshire rooster and a Barred Rock hen. Red Stars are a cross between a Rhode Island Red or New Hampshire rooster and a White Rock, Silver Laced Wyandotte, Rhode Island White, or Delaware hen.

Meat-Type Birds

Chickens developed as meat breeds grow much bigger and faster than egg-laying breeds and develop a carcass with an abundance of meat on it. This has been accomplished through genetic selection for fast growth and increased breast meat yield over many generations. However, these meat-type birds are very poor egg layers and should not be counted on to provide an adequate number of eggs. Several popular choices for meat-type production include:

- Cornish (used in most commercial broiler operations)

- Freedom Ranger

- New Hampshire

- Jersey Giant

- Java

- Naked Neck

Cornish birds make up the heart of the commercial broiler industry today. Cornish birds grow remarkably fast and yield large amounts of breast meat. They are poor egg layers but excel at meat production while maintaining very good feed conversions.

Freedom Rangers were developed in France in the 1960s. They are often cited as an alternative to the Cornish cross chicken. They are slower-growing than Cornish cross birds and are often used in traditional, sustainable, and environmentally friendly farming methods to ensure the highest quality chicken possible.

The New Hampshire breed originated in New Hampshire from selective breeding programs in Rhode Island Reds. They were developed more for meat than egg production. Adults weigh 6.5–8.5 pounds. They are chestnut-red in color, somewhat lighter than Rhode Island Reds. Hens are prone to go broody, and they make good mothers. New Hampshire hens lay brown to dark brown eggs.

The Jersey Giant breed was developed in New Jersey in the late 19th century. Jersey Giants are quite large as adults, weighing 10–13 pounds. They are calm and docile but require a large amount of feed and time to reach their full size. They are fairly cold hardy and lay large brown eggs. There are three varieties: black, white, and blue.

The Java is the second-oldest American chicken breed, behind only the Dominique. Adults weigh 6.5–9.5 pounds. Javas are particularly good foragers when allowed to free range. They are slow-growing but produce a good carcass and a respectable number of brown eggs. They are docile and hardy in bad weather. Javas come in three color varieties: black, mottled, and white. Javas are critically endangered today, as their numbers are quite low.

The Naked Neck is a breed of chicken that naturally has no feathers on its neck and vent. The breed originated in Transylvania and was later perfected in Germany. Their temperament is docile and friendly, although Naked Neck roosters can sometimes be aggressive. Hens may go broody, and those that do make excellent mothers. Adults weigh 6.5–8.5 pounds. They require less plucking than other meat-type breeds as they have approximately half the feathers of other breeds. They produce a meaty carcass. There are four color varieties in the United States: red, white, black, and buff. Naked Neck hens lay brown eggs.

Dual-Purpose Birds

If you are looking for both meat and egg production from your chickens, choose a good dual-purpose breed. Many backyard chicken enthusiasts choose dual-purpose breeds because they want a bird that will provide both meat and eggs. However, egg production and growth are negatively correlated. This means that if you select for one, the other one will likely suffer. For example, if we develop a chicken to grow fast and gain weight, we are decreasing the number of eggs that chicken will produce. Conversely, if we strive for a breed that will have good egg production and lay large eggs, we have decreased the growth potential and meat production capabilities of that bird. Fortunately, there are several popular dual-purpose breeds that do a good job of balancing acceptable egg numbers with reasonably good growth potential and meat production. Several popular dual-purpose breeds include:

- Rhode Island Red

- Orpington

- Dominique

- Plymouth Rock

- Wyandotte

- Brahma

- Delaware

The Rhode Island Red breed may be the most popular of the dual-purpose breeds. They were developed in Rhode Island and Massachusetts in the early 1900s. They are used more for meat than eggs but will continue to lay eggs into moderately cold weather. They are quite hardy and good foragers. They are also docile and friendly, making them a favorite of many backyard chicken keepers. Adults usually weigh 5.5–8.5 pounds. Rhode Island Reds have been used to produce many of today’s modern hybrids, including cinnamon queens and sex-links, among others. The hens lay brown to dark brown eggs.

Orpingtons are large-framed birds (7–10 pounds as adults) with very loose feathering that gives them a somewhat “fluffy” appearance. They originated in England in the late 1800s. Their temperament is calm and docile, but they do not forage well. Orpingtons come in a variety of colors (buff, blue, white, and black) and have very good mothering abilities. They lay brown eggs that can range from light to dark in color.

The Dominique breed (often called Dominickers) is considered the oldest “American” breed, originating in the colonial period. Adults weigh 4–7 pounds. Dominiques are docile, hardy, and good foragers. They have only moderate mothering instincts and lay brown eggs.

Plymouth Rock chickens were developed in America in the mid-1800s. Adults weigh 4–7 pounds. There are several varieties, including barred, white, buff, partridge, silver penciled, blue, and Columbian. They are docile and have good mothering instincts but are poor foragers. Plymouth Rock hens lay brown eggs.

The Wyandotte breed was developed in New York State in the late 1800s. They are quite cold hardy but do not do well in the heat. They weigh 5.5–8.5 pounds as adults. They come in several varieties. The original Silver Laced Wyandotte is also known as the “American Sebright” or “Sebright Cochin.” They are relatively docile and are a favorite of the show bird circuit. Wyandotte hens lay light to dark brown eggs.

The Brahma breed was developed in America from large fowls imported from China in the mid-1800s. Adults are quite large, weighing 8–12 pounds. They have feathers on their shanks and toes. Brahmas are extremely hardy and are good egg layers for their size. They stand the cold very well but are not ideal for warmer climates. They are slow-growing but good meat producers. Brahmas come in three varieties (light, dark, and buff) and lay light to dark brown eggs.

The Delaware breed was developed in 1940 by crossing off-colored Barred Plymouth Rock males and New Hampshire females. Adults weigh 5.5–7.5 pounds. They have a calm and friendly disposition and have well-developed egg and meat qualities. Delawares were part of the commercial broiler industry until the late 1950s when the Cornish cross birds took their place. They are good foragers and lay brown eggs.

Summary

Maintaining a flock of backyard chickens can have many benefits. Your chickens can provide enjoyment, entertainment, pest control, eggs, meat, garden fertilizer, 4-H and FFA projects for your children or grandchildren, and more. However, backyard chickens also require effort on your part. Plan ahead and know what you want before you start. If you live in town, make sure your city and neighborhood allow chickens. You must provide a safe environment to protect your birds from predators and the weather. Be aware that your birds will need care and attention every day, including weekends and holidays. Decide if you want egg birds, meat birds, or dual-purpose birds. Then make your choice of birds from a wide range of options, and, most importantly, enjoy the experience! A wealth of additional information on managing backyard poultry flocks can be found on the Mississippi State University Department of Poultry Science website at http://extension.msstate.edu/agriculture/livestock/poultry/small-flock-….

Publication 3036 (POD-02-20)

By Tom Tabler, PhD, Extension Professor, Poultry Science; F. Dustan Clark, Extension Poultry Health Veterinarian, University of Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service; and Jessica Wells, PhD, Assistant Clinical/Extension Professor, Poultry Science.